This blog is part of the series “Ignored Conflicts” by the Peace & Conflict program at Polis180.

The ongoing crisis in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is driven by a deadly interplay of armed rebellion, failed state institutions, and international complicity. The M23 militia’s recent takeover of Goma underscores the Congolese army’s systemic weakness, rooted in colonial legacies and decades of authoritarian rule. Meanwhile, over 7.8 million people are displaced, and international humanitarian aid has sharply declined. Rwanda’s renewed military backing of M23 reveals how ethnic narratives, security concerns, and economic interests – especially in mineral-rich areas – intertwine to perpetuate conflict. Despite evidence of illegal Rwandan involvement, European nations continue to invest in Rwanda’s mineral supply chains, effectively financing armed actors while underfunding the DRC. This double standard undermines the EU’s credibility and highlights broader geopolitical shifts that have accelerated since the U.S. scaled back its international commitments under the Trump administration. A sustainable solution requires Europe to align its values with its actions—through sanctions, supply chain oversight, military reform assistance, and robust civil society support. Only a coherent and value-driven EU policy can help break the cycle of exploitation and conflict in the Great Lakes region.

A blog by Adrian Zachariae

In late January 2025, the M23 rebel militia captured Goma, a major city in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and has since continued its military advance. Mass executions, sexual violence, and forced recruitment now define daily life in the affected areas. A key factor behind M23’s advance is the structural weakness of the Congolese military, the Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC): poorly trained, under-equipped, and with salaries of $100 a month, but often unpaid – many soldiers resort to looting and the illegal mineral trade. This weakness is not merely a result of recent failures: it is deeply rooted in the country’s postcolonial history. The institutional fragility of the FARDC dates back to the Mobutu era (1965–1997), when the military was deliberately undermined to prevent potential coups. Instead of building robust institutions, the Mobutu regime – often with tacit support from Western powers – prioritized authoritarian control and systemic plunder over sustainable nation-building.

Despite the absence of a full-scale war in recent years, the Congolese population continues to suffer from chronic instability, systematic violence, widespread poverty, and severe human rights violations – a reality persisting since the country’s independence in 1960. Currently, according to the United Nations, over 7.8 million Congolese people are internally displaced and millions more rely on humanitarian assistance. This vital support has been severely compromised by the Trump administration’s decision to significantly reduce USAID funding, cutting approximately 70% of international aid to the country. Essential services like healthcare, food aid, and programs aimed at strengthening civil society, education, and democracy have been critically affected. The consequences are particularly dire in Kivu, where recent M23 offensives have displaced over 700,000 people, overwhelmed hospitals, and severely disrupted humanitarian efforts due to persistent violence and logistical challenges such as the closure of Goma’s airport.

But how is it that the seemingly insurmountable spiral of violence and hopelessness has emerged in a country that, with its natural resources, could be one of the wealthiest in the world?

The answer lies partly within the question itself and partly in the country’s history. The Democratic Republic of the Congo has never genuinely been given the chance for political or economic stability and continues to struggle with the heavy legacy of colonial exploitation. The assassination of Patrice Lumumba, the country’s first democratically-oriented leader – carried out with Belgian complicity shortly after his election – and Mobutu´s CIA-backed rise convey a message that still rings true today: the Congo does not belong to the Congolese.

A history of violence: How colonialism and dictatorship divided the Congo

The thirty-year kleptocratic dictatorship under Mobutu is only partly to blame for the current situation in the DR Congo. One must look even further back to the colonial era, when Germany and Belgium colonized the present-day countries of Rwanda and the DR Congo, dividing the local population into two ethnic groups: the Hutu and the Tutsi. Originally, Hutu and Tutsi referred to social roles – farmers and herders – not rigid ethnic identities. Colonial rulers imposed a racist interpretation, classifying the Tutsi as more ‚white‘ and ‚European‘ – and therefore superior to the Hutu. By institutionalizing these ethnic divisions, colonial authorities granted Tutsi privileged access to education and political power, planting seeds for long-term resentment and future conflict. These tensions culminated decades later in the 1994 genocide, in which around one million people – predominantly Tutsi – were killed. Following Rwanda’s regime change, approximately 1.25 million Hutu fled westward into neighboring DR Congo (then Zaire), among them the so-called génocidaires, the perpetrators of the 1994 genocide. To this day, the Rwandan government cites the presence of these groups as a justification for its military involvement and influence in eastern Congo, accusing the DRC of providing refuge to those responsible for the genocide. Competing for land, influence, and control over abundant natural resources – such as gold, diamonds, cobalt, and coltan – various actors including displaced communities, local groups, rebel movements, and national armies have escalated tensions, fueling a complex and ongoing cycle of violence. This dynamic reflects the so-called resource curse, where countries rich in natural resources often experience intensified conflict, corruption, and economic instability rather than prosperity.

In the First Congo War (1996–1997), Mobutu was ousted, leading to the rise of Laurent-Désiré Kabila’s government in the DRC. However, this marked the beginning of ongoing conflicts that would culminate in the Second Congo War (1998–2003), often referred to as Africa’s World War. During this period, the DRC faced massive military interventions from nine neighboring countries, including Rwanda, Uganda, Burundi and Angola. While these interventions were justified as efforts to protect minority groups, such as Tutsi refugees in the DRC, the underlying motivations were primarily driven by the control of the country’s abundant mineral resources, including gold, diamonds, cobalt, and coltan. Rwanda, in particular, played a significant role, seeking to safeguard the Tutsi population and prevent the return of genocidal Hutu forces, while also pursuing its own economic and security interests in the region.

During this period, DR Congo lost control over vast areas, especially in the eastern provinces, turning them into battlegrounds for local groups and foreign powers. As a result, the country was effectively divided, with armed groups and neighboring countries controlling key resource-rich territories. Even the largest UN peacekeeping mission in the world, MONUSCO, established in 1999, failed to improve the situation. Instead, it came under heavy criticism for its inadequate resources, inefficiency, and alleged involvement in human rights violations. Both wars ultimately claimed around six million lives, making this conflict one of the deadliest in modern history.

The east in uprising: Who profits from the chaos in the Congo?

The Third Congo War escalated between 2006 and 2009 when the rebel group National Congress for the Defense of the People (CNDP), led by Laurent Nkunda, intensified its fight against government and UN forces. Officially, the CNDP aimed to protect Congolese Tutsi communities from the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), a militia primarily consisting of Rwandan Hutu fighters involved in the 1994 genocide, who had since operated from eastern Congo. The CNDP accused the Congolese army (FARDC) of cooperating with the FDLR, a claim supported by various reports, which Rwanda then used to justify its military support for the CNDP, citing ongoing security threats posed by the FDLR’s presence.

In March 2009, a peace agreement was reached, recognizing the CNDP as a political party and integrating its fighters into the FARDC. However, lasting peace remained elusive, due to unresolved issues such as ethnic tensions, resource competition, and mutual distrust between the Congolese government and former rebels. In 2012, former CNDP members founded the rebel group M23 after accusing the government of violating terms of the agreement, particularly regarding promised integration and political representation. The militia briefly captured the provincial capital Goma but was repelled in 2013 by a UN intervention force. From 2022 onwards, the conflict flared up again: Rwanda resumed its covert support of the M23, providing weapons and logistical assistance. M23 now controls strategic mining areas, notably the coltan-rich Rubaya region, monopolizing mineral extraction, issuing mining permits, and taxing local miners. The resources are often transported to Rwanda, aligning with Rwanda’s economic interests and financing M23’s military activities. These developments underscore how the M23 serves multiple purposes for Rwanda: as a military proxy to address perceived security threats, and as an economic tool to exploit the mineral wealth of the DRC.

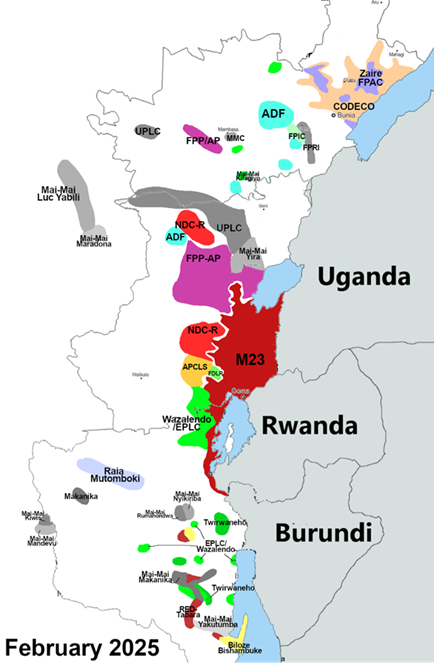

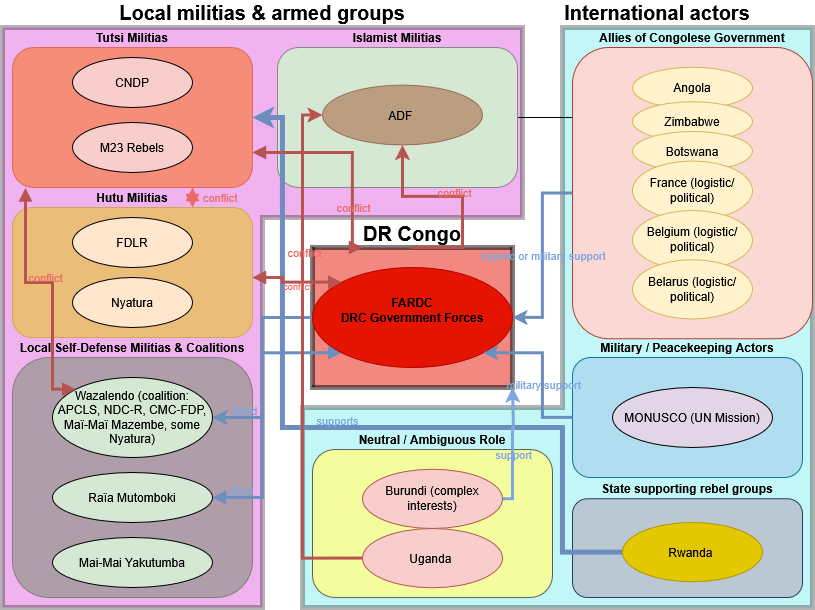

Today, over 120 armed groups are active in the eastern DR Congo, particularly in the resource-rich Kivu region. Rwanda remains central, having twice invaded the Congo, ostensibly to protect the Tutsi population and neutralize Hutu militias. According to a UN report, currently up to 4,000 Rwandan soldiers are fighting alongside M23. Congolese President Félix Tshisekedi rules out concessions but faces limited options against the heavily armed and technologically advanced militia. Despite the UN mission MONUSCO’s presence, the FARDC remains ineffective and even collaborates with militias like the FDLR, worsening instability through involvement in illegal resource trading.

The current conflict is also closely linked to a military agreement between Uganda and the DR Congo, which allows Ugandan troops to operate against the Islamist terrorist organization Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) on Congolese soil. In exchange, Uganda gained the right to develop infrastructure, such as roads, in resource-rich eastern Congo. Rwanda perceived this cooperation as a threat to its own economic and geopolitical interests in the region, potentially enhancing Uganda’s influence and access to valuable minerals. This likely prompted Rwanda to reactivate the M23 militia, aiming to counterbalance Uganda’s expanding influence in the region.

Due to profound weaknesses within the Congolese army (FARDC), the government has increasingly relied on proxy warfare, notably by supporting the Wazalendo coalition—a loose alliance of armed groups formed specifically to combat M23. This strategy has heightened violence, deepened factional rivalries, and further destabilized the region. The already opaque network of armed actors is further complicated by dozens of local self-defense groups known as Mai-Mai militias. Originally formed as community defense units against external threats, these militias have evolved into diverse factions, each driven by distinct political, ethnic, or economic interests, frequently competing over territory and natural resources.

Currently, direct negotiations are being held in Doha between the DR Congo, the M23 rebel group, and Rwanda, but expectations for a breakthrough remain low, as previous mediation attempts under Angola’s leadership ended without tangible results. Deep mistrust persists between the involved parties: M23 continues to assert its legitimacy, demanding political recognition and improved representation, while President Tshisekedi insists on a complete militia withdrawal as a prerequisite. Rwanda vehemently denies accusations of military support for M23, consistently labeling it as a purely Congolese movement, despite extensive evidence documented by independent observers and UN investigators. Given these entrenched positions and mutual accusations, reaching a sustainable resolution in Doha remains highly challenging.

Illegal Exports, Legal Investments: Europe’s Selective Ethics in the Congo Conflict

This mix of geopolitical interests, state failure, and international indifference has created a region where violence is commonplace and economic exploitation is systematically tolerated – often with tacit approval from international partners. While blood continues to be spilled in eastern DR Congo, elsewhere the trade in resources financing this war thrives.

An illustrative example of this contrast is the European Union’s divergent approach toward mineral trade: On the one hand, the EU officially supports stability and development in the DRC; on the other, it deepens economic cooperation with Rwanda through substantial investments in mineral supply chains. Although economically significant for both the EU and Rwanda, this partnership raises serious questions about political consistency and moral responsibility.

In February 2024, the EU signed a “Memorandum of Understanding” with Rwanda, securing access to raw materials in return for significant investments – around €900 million from the EU’s Global Gateway initiative – in Rwanda’s mineral supply chains and infrastructure. By comparison, the EU allocated only approximately €424 million to the DR Congo for 2021–2024, less than half that amount. It is, of course, more profitable to invest in a stable country like Rwanda. However, Rwanda exports more raw materials than it can extract based on its geological composition. Importers should be aware of this discrepancy following due diligence or compliance processes. Yet countries or regions such as the EU continues to accept minerals of opaque background, using public funds to finance illegal trade and indirectly support militias.

The EU’s collaboration with Rwanda appears too valuable to abandon, particularly given that European funds also support Rwandan military operations for counterterrorism efforts in Mozambique. Moreover, Rwanda is repeatedly considered by various European countries as a partner to host refugees, following the example set by the UK’s agreement to relocate asylum seekers there under inhumane deportation policies. Despite acknowledging Rwanda’s role in the DRC conflict and imposing sanctions on Rwandan military and M23 commanders in March this year, the EU remains reluctant to reconsider its raw materials agreement. This hesitation persists despite threats by EU High Representative Kaja Kallas to reconsider the agreement and mounting pressure from Belgium, underscoring internal divisions and inconsistencies within the EU itself.

A union of values? Europe can and must dare to do more

The central factor in this war is the battle for resources, facilitated by colonial structures, the instrumentalization of regional conflicts, and driven by foreign influence. The situation has further deteriorated since Donald Trump’s presidency, during which the United States, despite being the world’s wealthiest nation, significantly retreated from its humanitarian commitments and now ruthlessly demands resources in exchange for security. The withdrawal has not only deepened human suffering but also contributed to a security vacuum, increasingly filled by local militias and external actors. As a result, China’s influence in resource extraction and infrastructure investments has grown markedly, and Rwanda has expanded its strategic reach. The EU, compelled by these shifts, is struggling to recalibrate its diplomatic and financial commitments to fill this void, raising concerns about Europe’s capacity and willingness to provide a credible geopolitical counterweight in the region.

To genuinely disrupt the seemingly endless spiral of violence in eastern Congo, the EU must decisively employ tools it already possesses. Rather than continuing its superficial symbolic politics, it should impose targeted sanctions explicitly targeting Rwandan units, logistics firms, and traders facilitating illegal conflict-mineral trade in coltan and gold. Parallel to this, a clearly defined and robust military advisory mission—perhaps a revitalized EUSEC operation—should secure regular salaries for Congolese soldiers and provide essential military training and organizational support. Equally critical is rigorous supply chain regulation coupled with anti-corruption initiatives, such as mandating provenance certificates for all minerals sourced from conflict regions and establishing EU-backed real-time monitoring of Congolese mining revenues to expose and curtail systematic looting by armed groups. Simultaneously, the EU must directly strengthen civilsociety, providing immediate emergency funds for local peace-building initiatives and women’s groups, fostering civilian resistance against violence and exploitation. Finally, the EU must elevate its currently passive diplomatic approach, establishing annual high-level summits involving the EU, the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR), and the United Nations, at which all parties publicly commit to verifiable benchmarks for conflict resolution and resource governance. Only when the EU translates rhetoric into concrete actions can it demonstrate that its core values exist not merely on paper but also in practice.

Adrian Zachariae has been a member of Polis180 since early 2025. He studied political science with a focus on security policy at Sciences Po Strasbourg, gained initial experience in international cooperation, and now works in the field of artificial intelligence. His interests lie at the intersection of foreign policy, societal change, and the question of how technology shapes political processes – for better or worse.

Footnotes

Map 1: Map of the Kivu conflict showing armed group incidents between March 2024 and February 2025.

Created by Borysk5 based on ACLED data. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

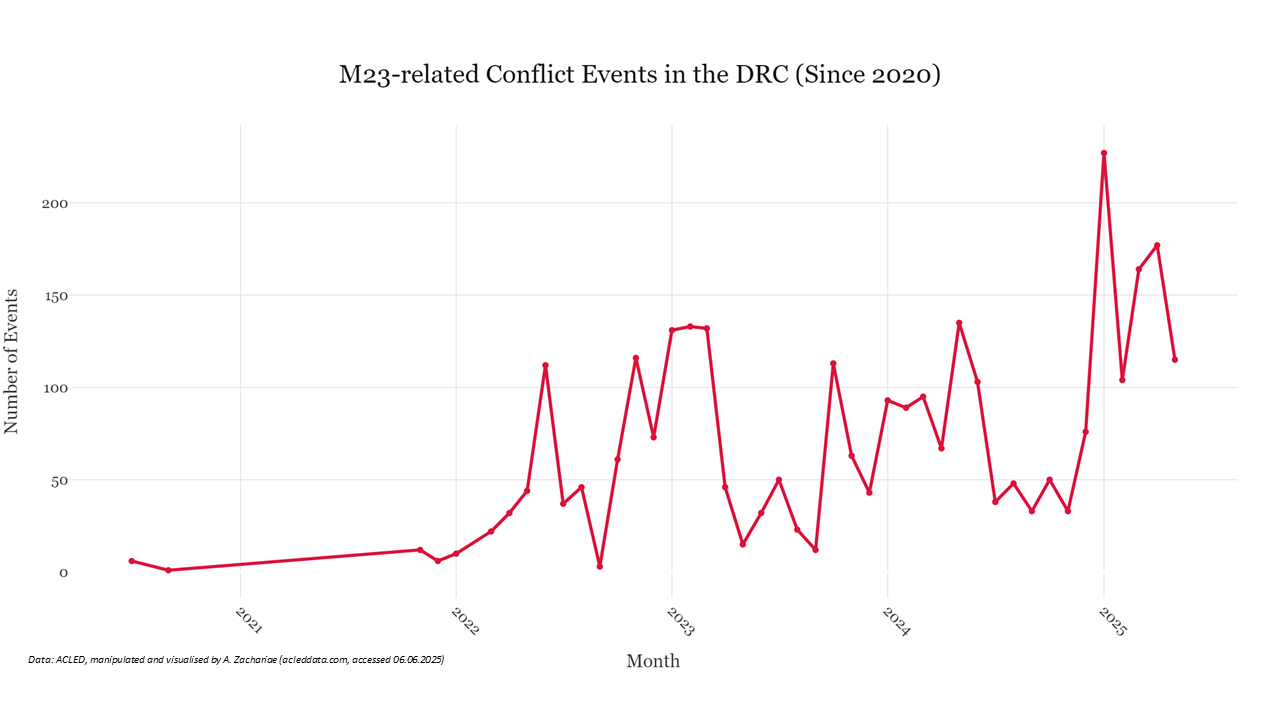

Image 1: M23-related conflict events in the DRC (since 2020); Data source: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED).

The re-emergence and escalation of M23 activity from 2022 onwards is clearly visible, with 2025 marking a new peak. This trend correlates with the group’s growing military strength and territorial ambitions.

Map 2: Conflict density in the DRC since 1997; Data source: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED).

This map shows the spatial distribution and intensity of reported violent events in the DRC since 1997, revealing long-standing conflict corridors, particularly in eastern provinces like North Kivu and Ituri.

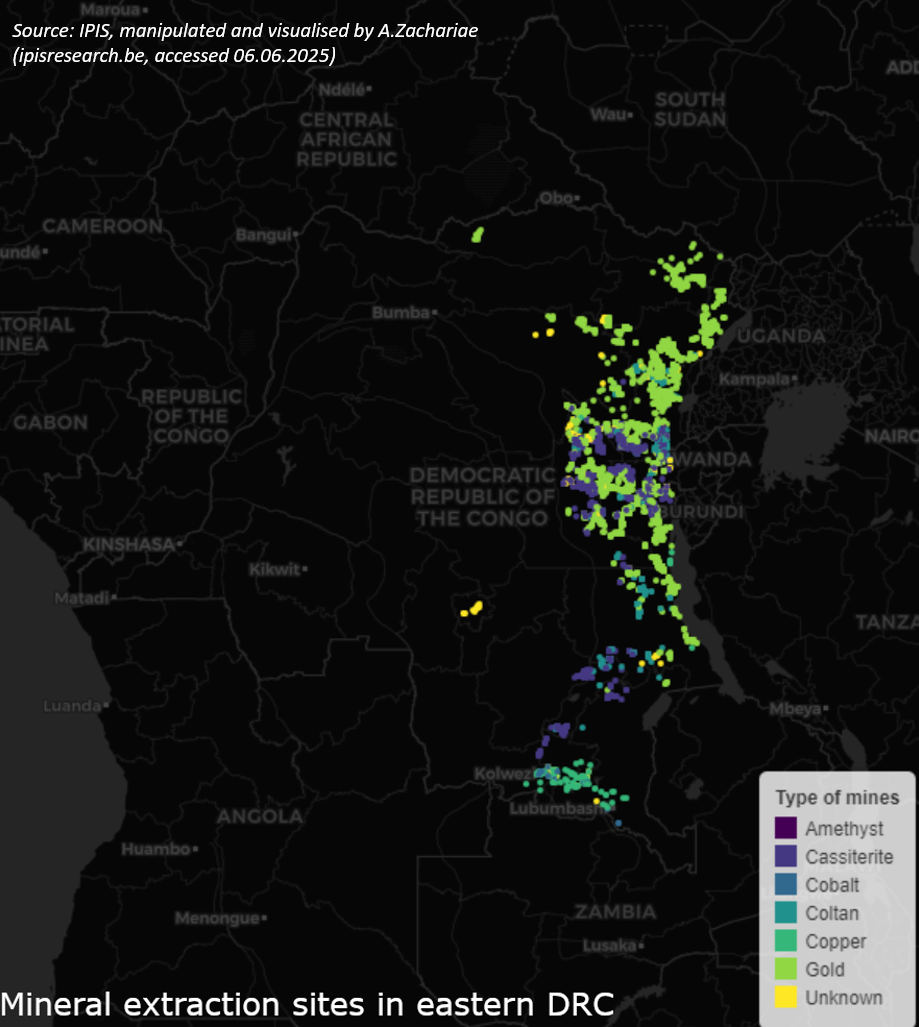

Map 3: Mineral extraction sites in eastern DRC; Data Source: The International Peace Information Service (IPIS).

The distribution of artisanal mining sites closely mirrors the geography of conflict, particularly in areas rich in gold, coltan, and cassiterite – highlighting the spatial overlap of violence and resource extraction.

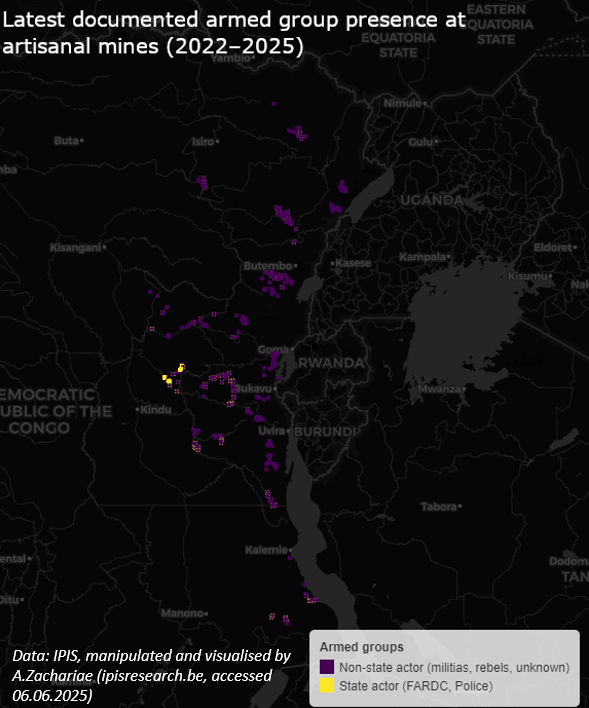

Map 4: Latest documented armed group presence at artisanal mines (2022-2025); Data Source: The International Peace Information Service (IPIS).

This map shows only the most recent documented presence of armed groups at mining sites, distinguishing between state and non-state actors. The limited coverage underscores how much current control remains unverified.

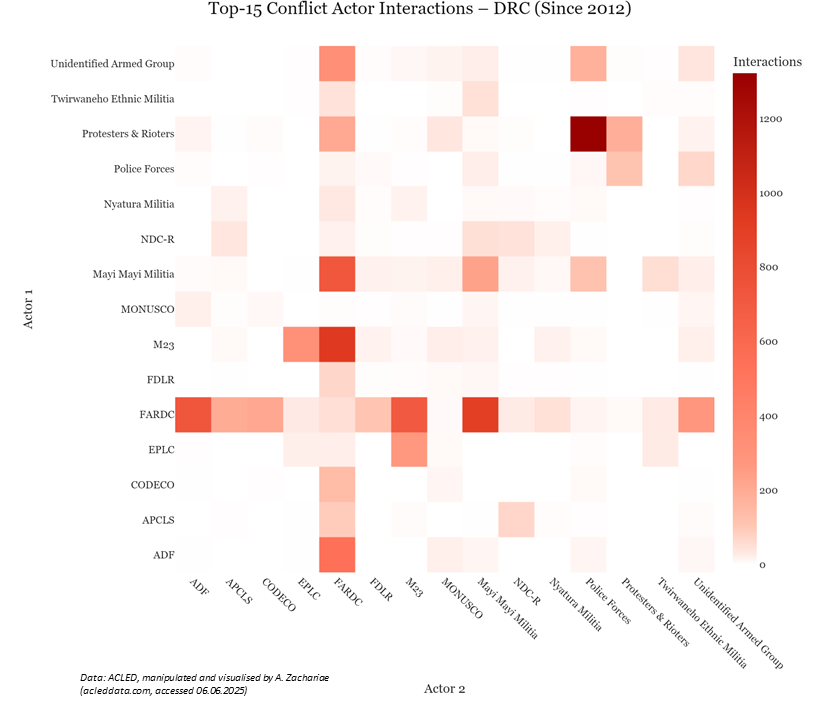

Image 3: Conflict Actor Interactions – DRC (Since 2012); Data source: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED).

Interaction matrix of the top 15 conflict actors since 2012. The dominance of state actor FARDC in horizontal and vertical interactions indicates its central role in both engagements and confrontations with a broad range of actors.

Previously from the blog series “Ignored Conflicts”

-

Between Neocolonialism and Jihad: The Overlooked Conflict in Burkina Faso

-

From Revolution to Ruin: Haiti’s Plight and the World’s Apathy

-

The High Cost of Ignoring Nagorno-Karabakh: How Unresolved Grievances and Geopolitical Interests Fuel Future Conflict

-

The Unfinished Breakaway: Why Somaliland Matters to Global Stability

-

Raw materials, rebellion, Rwanda: The multilateral crisis in eastern DR Congo and its global implications

The Polis Blog serves as a platform at the disposal of ‘Polis180’s & ‘OpenTTN‘s members. Published comments express solely the ‘authors’ opinions and shall not be confounded with the opinions of the editors or of Polis180.

Zurück