June 7th 2023

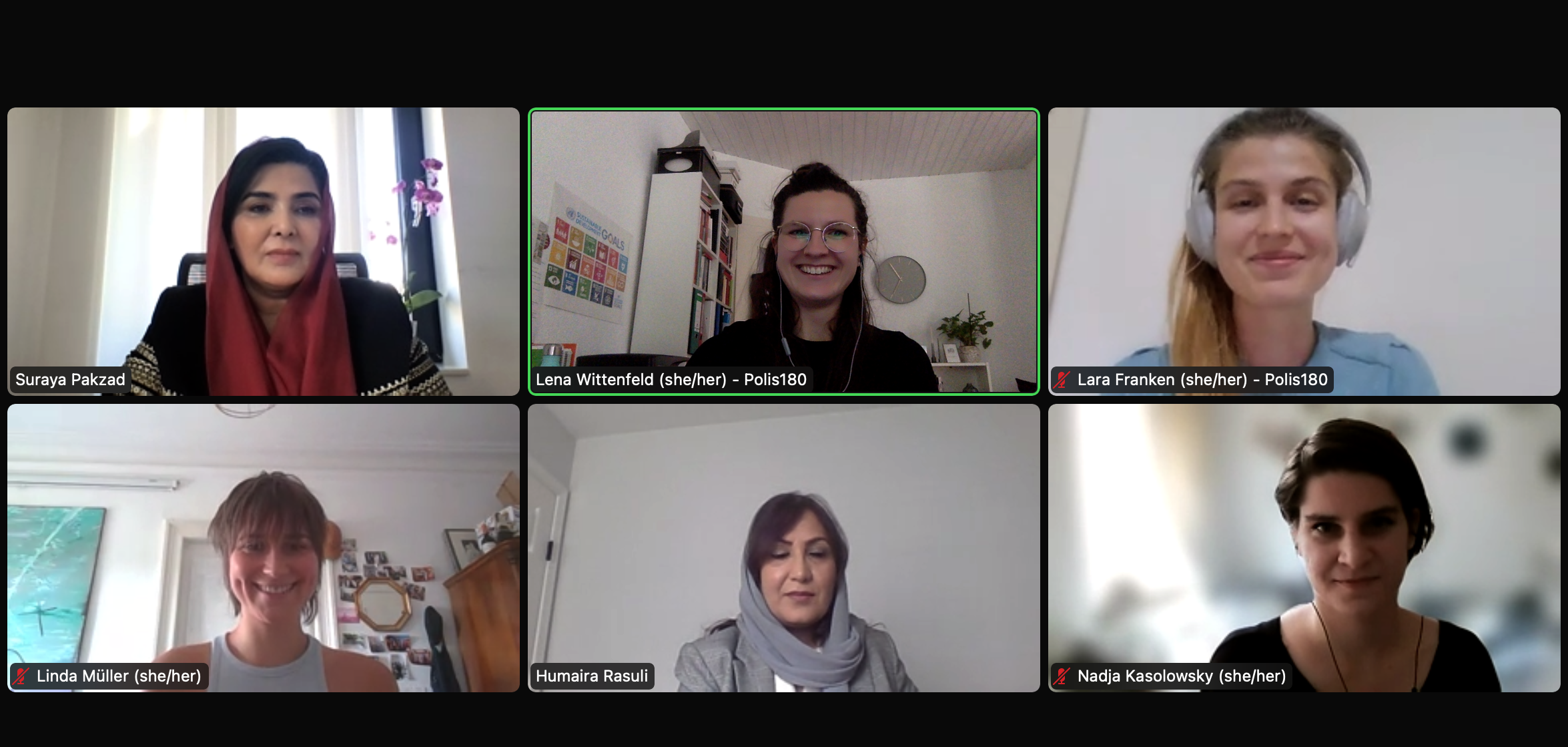

Following our kick-off event “Rights, Resources, Representation – Focusing on the New BMZ Strategy for a Feminist Development Policy” in the event series on Feminist Development Policy, organized by the programs Gender and International Politics and De_Constructing Development, our aim was to discuss the BMZ’s strategy on a feminist development policy from an Afghan postcolonial perspective. Together with Humaira Rasuli and Suraya Pakzad, we critically questioned whose voices are heard, who is visible and who dominates not only the strategy’s conception and the related public discourse but also development policy in Afghanistan in general. Thereby, our event was meant to understand and reveal blind spots and (neo-)colonial practices as well as gaps and weaknesses of the BMZ’s strategy and development policy.

Humaira Rasuli is an Afghan human rights lawyer and activist with additional training as a trauma counselor. She is the Executive Director and Co-founder of Women for Justice Organization, and until 2018 she was also the executive director of Medica Afghanistan.

Suraya Pakzad is an Afghan human rights activist currently living in Germany. She is currently the Executive Director of the Voice of Women Organisation, which she founded herself. This emerged from a project in which she ran a covert school for girls in Kabul during the Taliban.

Our speakers began to outline how they define feminist development policy for themselves – professionally and personally. Emphasizing the agency that is inherent to feminist development policy, they define it as a movement for taking actions and for guaranteeing equality so that women have the same rights, have access to resources and are able to enjoy dignity, respect, and security. Thereby, feminist development policy is regarded as a multidimensional and multi-level undertaking which includes among other things the individual level but also the family and society. However, the speakers highlighted the heterogeneity and variability of feminist development policy as well as its interwovenness with transformative politics of gender equality. In Afghanistan, feminist organizations are still in process to adapt and create strategies to be able to protect more women and girls which is especially challenging for local organizations. Relating their definitions and work to the German BMZ strategy, Suraya and Humaira see potential in the strategy to create concrete opportunities for action and transformation if the new BMZ strategy increases support for feminist policies and organizations. To ensure the inclusion of marginalized groups on various levels, both stress that the BMZ should actively engage in inclusive participation, capacity building initiatives, and a diverse approach to make its strategy sustainable. Problems of exclusivity have already been visible during the conception and consultation phase. While the Afghan diaspora in Germany carries a lot of knowledge, expertise, and experience and could provide insights, the speakers revealed that the diaspora was, to their knowledge, not invited in the process despite their ability to strongly contribute to various processes and to enrich the conversation and improve the strategy. However, both speakers emphasized that participation is integral to the feminist development policy strategy’s success.

In the following, the role of international solidarity and collaboration as well as of Germany was critically reflected upon. Here, the challenges for the global community to be involved in Afghanistan without being in cooperation with the Taliban were acknowledged. Yet, it was thoroughly emphasized that sustainable action is needed that includes feminist activism and long-term strategies and processes. Thereby, our speakers addressed certain problems. For once, an intense brain-drain from Afghanistan to Europe and the US takes place that among others also includes civil society leaders. Consequently, these actors are missing in Afghanistan to sustainably build up structures and to lead processes and actions. Further, development cooperation should include the Afghan diaspora as actors within the diaspora often have easier access to information and better relations reading the current situation and needs in Afghanistan. Hence, a feminist development policy should include those who have left Afghanistan as well as build upon various sources of knowledge to, for instance, ask women what is needed to build human rights structures and to further and diversely promote women rights. Focusing on (long-term) capacity-building of the Afghan civil society and on the development of feminist strategies, the Germany’s partnership with Afghanistan’s (civil) society needs to be strengthened, local and diaspora expertise needs to be acknowledged and consulted and comprehensive action needs to take place by, for instance, establishing a national or multilateral as well as German-led task-force to unit Afghanistan’s civil society and government. Moreover, it was emphasized that cooperation must also be driven forward with Muslim countries that have made significant progress for women’s rights within the Islamic legal framework as a West-led, or Western approach does not help due to Afghanistan’s history of Western occupation and (neo-)colonial notions. Following other Muslimstates’ progressive practices, for instance, Islamic legal arguments have been utilized in Muslim family laws to ban child marriage, to equate marriage age for both girls and boys, to give equal divorce rights to men and women, to ban or conditionalize polygamy, to enhanced women’s custody rights, and to increase women’s education and employment.

Overall, the discussion illustrates that the BMZ’s strategy needs to build upon concrete actions and to critically examine its implication to reveal postcolonial power-dynamics, historicity and how the BMZ’s approach is genuinely postcolonial. Thus, transformative change at structural level is necessary upon which the BMZ’s approaches, strategies, and priorities may shift. Further, it is important to ensure that voices of marginalized communities, local feminists, and grassroot organizations are heard and actively included as well as to ask ‘whose voices are heard and whose voice should be heard?’ to counter women’s invisibility. Thereby, the trust on local civil society organizations has to increase as they bear deep knowledge, experience, connection, and access. In this regard, it also has to be examined how sanctions impact civil society’s funding and development programs. Hence, donors and donor countries should go to details of their work to properly understand practical challenges and to encourage and strengthen resilience while counteracting hierarchies and power systems that are reproduced in their work.There are a lot of women inside and outside of Afghanistan that dedicate their lives to Afghan civil society organizations. Even though their voices are there, they are not always united in a homogenous diaspora nor in Afghanistan. However, especially women are confronted by numerous challenges and threats by the Taliban but also by the international community. Afghan women fight a lot of different fights simultaneously and on different levels and there is a lot of work still to do that also needs support from others, for instance through development aid. However, the international community’s support – and hence the BMZ’s work – not only needs to increase significantly but also needs to strategically act in favor of Afghanistan’s positive development by evaluating situatedness, dominant structures, narratives and actions more careful and thoughtful as well as through a strong feminist and postcolonial lens.

This event was organized by Polis180’s program Gender and International Politics and is part of the event series on Feminist Development Policy.

Event report written by Lena Wittenfeld

Event organization by Lara Franken, Nadja Kasolowsky, Linda Müller & Lena Wittenfeld

Zurück