This blog is part of the series “Ignored Conflicts” by the Peace & Conflict program at Polis180.

Nagorno-Karabakh may have fallen to Azerbaijan in 2023, but the conflict is far from over. Decades of ethnic tensions and geopolitical power plays have left deep scars that continue to unfold in regional and international courts today, while over 100,000 Karabakh-Armenians remain displaced. The EU’s failure to act decisively – prioritizing energy security over humanitarian responsibility – has only exacerbated the situation. This blog post explores how colonial decisions, geopolitical maneuvering, and international inaction led to today’s status quo. Looking ahead, the risk of renewed conflict, particularly over Azerbaijan’s ambitions for the Zangezur corridor, remains high, threatening further instability in the South Caucasus with lasting consequences for regional and European security.

A blog by Merritt Fedzin and Linus Steinmetz

Imperial cartography: the ethno-colonial background to the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

After the collapse of the Russian Empire, nation building, independence declarations and border demarcation took place in the South Caucasus, including the region of Nagorno-Karabakh (from Russian, meaning “mountainous” Karabakh), also known under its ancient Armenian name Artsakh. With the founding of the Soviet Union, Nagorno-Karabakh was promised to be incorporated into the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR), but Stalin allegedly reversed the decision in 1923. Nagorno-Karabakh instead became an Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) under the Azerbaijan SSR, despite 95% of its population being of Armenian origin. The move was likely part of the Soviet divide-and-rule strategy – suppressing nationalism within the local populace to avoid ethnic-based claims to power.

The territorial conflict shaped by ethnic and structural dimensions, which was largely dormant under Soviet rule, resurfaced in the late 1980s as the Soviet Union began to weaken. In 1991, Nagorno-Karabakh declared its de-facto independence and established the self-proclaimed ethnic Armenian Republic of Artsakh. However, the breakaway republic remained internationally unrecognized – even by Armenia, which feared international condemnation – and was still legally considered part of Azerbaijan under international law. This internationally unrecognised independence left the predominantly ethnic Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh in a decades-long state of limbo: heavily dependent on close economic, political, and military ties with Armenia, but legally considered Azerbaijani territory already before Baku’s 2023 military offensive.

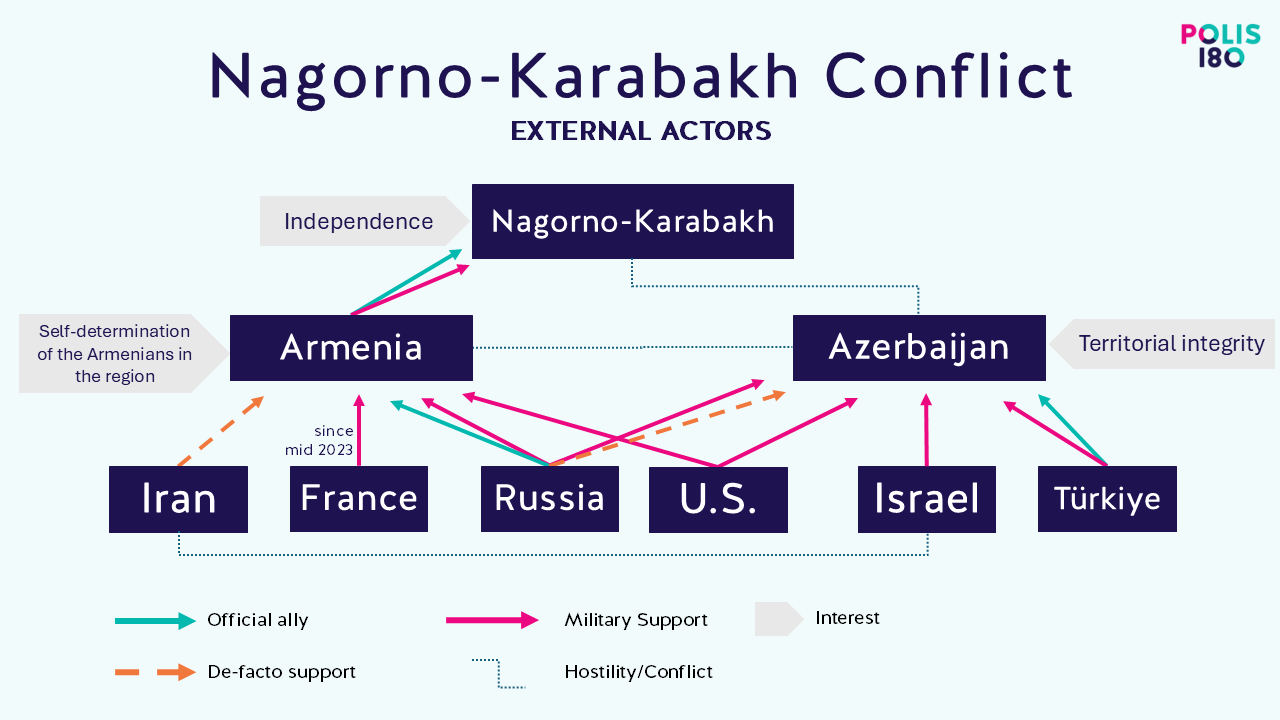

International actors shaping the conflict were largely Russia, Iran and Türkiye, given that the region was historically shaped by the Persian, Russian and Ottoman Empires. From supplying weapons and humanitarian aid to negotiating ceasefires and establishing peacekeeping and monitoring missions, Türkiye and Russia were the most influential players in the decade-long conflict surrounding the region’s independence. Western-European policymakers have been largely absent due to a lack of political, historical and ethnic ties although the United States and France have close diplomatic ties to Armenia primarily due to diaspora communities in the respective countries.

War of opportunity: Azerbaijan’s military takeover of Nagorno-Karabakh in 2023

The often-claimed final ‘battle of the conflict’ began with a lightning offensive by Azerbaijan into Nagorno-Karabakh in September 2023. With their rapid military success, Azerbaijani forces gained full control of the occupied territory of Nagorno-Karabakh and began to forcibly displace over 100,000 Karabakh Armenians. In just one week, almost the entire population of Nagorno-Karabakh fled to Armenia. The Republic of Artsakh, along with all its governing institutions, was officially dissolved on 1 January 2024.

But what created this opportunity in the first place? In the aftermath of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War in 2020, the EU attempted to negotiate a ceasefire settlement but ultimately failed and left it to Russia to finalize the agreement between the parties. This included the establishment of a Russian peacemaking mission. It is safe to say that this mission has failed, with Azerbaijan disrupting the ‚peace‘ through the use of force and altering the agreed status quo in 2023. A critical factor in Azerbaijan’s decision to launch its so-called ‚anti-terrorist mission‘ were the Russian peacekeepers themselves. Before Azerbaijan launched its offensive, Russian troops passively allowed Azeris, posing as eco-activists, to blockade the Lachin Corridor – the sole link between Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh – cutting off vital supplies and endangering thousands. This weakened Nagorno-Karabakh’s authorities and population, further shifting the balance of power and creating an opening for Azerbaijan to attack while Russian ‘peacekeepers’ looked away.

It could be argued that the Russian peacemaking mission never had the intention of making or even keeping peace. Russia’s interest in destabilizing the region and continuing its historical divide-and-rule strategy clearly outweighed its obligations as a peacekeeper. It therefore willingly accepted a defeat of its official ally Armenia, in order to strengthen ties with Azerbaijan and Türkiye – a NATO member and western ally -, who as a trio share the same foreign and security policy goal to minimise Western or European influence in the region. The West’s disinterest and lack of careful analysis of Russia’s behaviour both, in advance and in the aftermath of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh war in 2020, enabled Russia’s safe passage to promote these interests. Russia’s wider geopolitical and ideological agenda and its policy to continue controlling former Soviet satellite republics has undermined a true ‘peacemaking’ mission and led the conflict to an ‘end’, where thousands of inhabitants of Nagorno-Karabakh were forced to leave their homes.

The EU’s Willful Blindness: Strategic Interests Over Moral Responsibility

The conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh is an example of an “ignored conflict” on several levels, in that it has been actively ignored by the EU because addressing it would be politically, economically, and morally inconvenient to deal with – apart from the fact that it does not pose an immediate security threat to the Union.

Despite its ambitions to mediate after the 2020 war, the EU’s efforts proved ineffective due to a lack of political will, ultimately failing to prevent Azerbaijan’s 2023 offensive and the mass displacement of Karabakh’s Armenians. Even after the armed offensive, EU member states failed to muster a strong response, allowing Azerbaijan’s President Aliyev to dismantle any path toward a sustainable peace. The EU’s engagement was limited to verbal condemnations, calls to halt military action, and a €5 million humanitarian aid package – these however were far from the decisive action the situation warranted. The situation was exacerbated by Europe’s failure to engage meaningfully in the region – both before and after the 2020 war – leaving Russia to act as an unreliable broker and provider for peace.

Morally, confronting Azerbaijan’s aggression would require the EU to acknowledge its own passivity in the run-up to the crisis. The ease with which the EU turned a blind eye to the forced displacement of civilians highlights a preference for moral convenience over difficult foreign policy choices.

At the heart of the EU’s reluctance was its growing reliance on Azerbaijan’s fossil gas after cutting ties with Russian energy in response to the Ukraine war. The 2022 EU-Azerbaijan gas deal, which promised to double imports by 2027, cemented Azerbaijan’s strategic importance and made President Aliyev an indispensable partner at a time of European energy vulnerability. This gave Baku unprecedented leverage over the EU in other policy areas such as Nagorno-Karabakh, which was masterfully used during the 2023 offensive to the detriment of the Karabakh population. The EU’s unwillingness to apply economic pressure or even threaten sanctions demonstrated that Azerbaijan’s geopolitical value far outweighed the fate of Karabakh’s Armenians.

The Armenian-Azeri tensions will last – regardless of the status of Nagorno-Karabakh

Now, one might ask: is Nagorno-Karabakh still a conflict if Azerbaijan fully regained control of the territory through military means in 2023? We argue that, yes, the conflict remains unresolved. A conflict does not end simply because one side has achieved military dominance or because territorial control is now in line with international law.

More than 100,000 Armenians were forced to flee their homes, and their grievances have not disappeared. For many, the experience of violent displacement will shape their identity, with future generations grow up seeing “the other” as responsible for their suffering, and while Azerbaijan settles a new Azeri population in Nagorno-Karabakh. The underlying tensions of the conflict persist, both at a societal level and in legal disputes, as Azerbaijan and Armenia continue to challenge each other before international and national courts. Currently, Azerbaijan is conducting trials against former Artsakh officials, who were detained as political prisoners after its 2023 offensive. They face a range of charges including genocide, terrorism and war crimes, which Azerbaijan is trying to spin to its own advantage. Azerbaijan is also destroying Armenian heritage sites in the territories it has gained control over since 2020. For the local population the conflict has not been resolved, but is very much present in their daily lives – it has merely been ignored by the EU.

Lastly, claims that Azerbaijan’s offensive in 2023 was the final battle of the decades-long conflict may be premature. Although Azerbaijan is in full military control of Nagorno-Karabakh, and Armenia is unlikely to prepare any attempts to regain control given its military inferiority, tensions over territory remain high elsewhere. Azerbaijan has been openly announcing plans to construct the “Zangezur” corridor between its main territory and its exclave, the Autonomous Republic of Nakhchivan. Divided by an 80-130 km strip of Armenian territory, Azerbaijan has long been demanding access to and control of the corridor, while Armenia has signalled its willingness to allow transport links throughout the region but opposes a corridor that it does not control. The dispute over the corridor is likely to continue , if not escalate, in the future. In light of the fact that Azerbaijan’s President Aliyev has recently been accusing Armenia of being a fascist state, and to be preparing a “war of revenge” – rhetoric also used by Russia to attack Ukraine – military tensions may rise in the short to medium term. Baku has also criticised France for selling arms to Armenia, and thus supporting efforts to prepare for war. It appears that Baku wants to place the responsibility for any conflict on Armenia and its supporters, possibly using this rhetoric to legitimize any kind of military action from its own side.

Ignoring the ongoing existence of conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan would be detrimental for European policymakers. Grievances and ethnic tensions remain, as do claims to territorial control and integrity. This is particularly true for transport links to the autonomous republic of Nakhchivan. EU policymakers must take into account past injustices and ongoing disputes in the South Caucasus if they are to develop a sustainable and just foreign policy for the coming decade – and prevent new military confrontations at the expense of local populations.

Linus Steinmetz has been a member of Polis180 since January 2025 and publishes on topics including Eastern Europe, the South Caucasus and climate diplomacy. He studies political science and economics in Berlin and Paris. His research focuses on climate security, European security policy and authoritarian regimes in Eastern Europe and Eurasia.

Merritt Fedzin joined Polis180 in 2021 and has been a member of the board since July 2024, where she is responsible for the publications and international affairs departments. Merritt studied European Studies, International Security and Conflict Studies in Magdeburg, Berlin and Istanbul. In her research she focuses on security and conflict dynamics from Central to Western Asia and Africa.

Previously from the blog series “Ignored Conflicts”

-

Between Neocolonialism and Jihad: The Overlooked Conflict in Burkina Faso

-

From Revolution to Ruin: Haiti’s Plight and the World’s Apathy

-

The High Cost of Ignoring Nagorno-Karabakh: How Unresolved Grievances and Geopolitical Interests Fuel Future Conflict

-

The Unfinished Breakaway: Why Somaliland Matters to Global Stability

-

Raw materials, rebellion, Rwanda: The multilateral crisis in eastern DR Congo and its global implications

The Polis Blog serves as a platform at the disposal of ‘Polis180’s & ‘OpenTTN‘s members. Published comments express solely the ‘authors’ opinions and shall not be confounded with the opinions of the editors or of Polis180.

Zurück