This blog is part of the series “Ignored Conflicts” by the Peace & Conflict program at Polis180.

Haiti is in a state of near-total collapse, overshadowed by gang violence, political chaos and a humanitarian disaster. The country’s crisis, rooted in colonial exploitation and failed foreign interventions, requires urgent and lasting solutions.

A blog by Elanur Alsaç and Carlos Apel

“Honestly, it is Haitians who killed Haiti by letting in drug trafficking”. This recent comment from the French president Emmanuel Macron on November 21, 2024 regarding Haiti’s spiraling humanitarian catastrophe is not only dangerously simplistic but false. The current situation represents the culmination of long-standing issues, rooted in Haiti’s colonial past and exacerbated by modern challenges, creating a multifaceted crisis that defies simple solutions. Haiti has not simply reached a crisis – it has descended into near-total collapse. Widespread violence, especially escalating sexual violence, political instability, and humanitarian crises are plaguing the nation. This Caribbean nation’s struggle is not merely a product of recent events but a complex tapestry woven from centuries of exploitation, systemic inequalities, and recurring natural disasters.

Source: Pellegrini, S. (16 October 2024). “Viv Ansanm: Living together, fighting united – the alliance reshaping Haiti’s gangland” Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). http://acleddata.com/2024/10/16/viv-ansanm-living-together-fighting-united-the-alliance-reshaping-haitis-gangland/ © 2025 ACLED. All Rights Reserved. Used with permission from ACLED.

Another deadly legacy of colonial history

Since the Spanish colonisation in the 15th century, the island of Hispaniola has endured a tragic history of deadly interference by colonial and occupying powers, leading to political and economic instability, violence and massacres, compounded by devastating environmental disasters such as earthquakes and hurricanes. In 1804, Haiti became the world’s first black-led republic and the first independent Caribbean state after a successful slave rebellion against French colonial rule. However, this hard-won freedom came at an enormous cost. France, with the backing of other colonial powers, demanded that Haiti pay reparations for the loss of slave labor and property. This “independence debt” amounted to 100 million francs (equivalent to $21 billion today), a sum Haiti was forced to borrow from French banks at exorbitant interest rates. It took Haiti until 1947 to finally pay off this debt by spending 80 percent of its revenues. Furthermore, the former colonial powers transformed huge parts of Haiti into sugar cane plantation, which has rendered large parts infertile. All this leaves a legacy of underdevelopment and financial instability that continues to affect the nation today. Therefore, historically oblivious statements by the French president, such as the one outlined above, are particularly to be condemned.

Haiti’s Enduring Struggle for Stability and Sovereignty

In addition to the massive debt burden, Haiti has experienced repeated coups, dictatorships and foreign interventions that have weakened the country’s institutions and economy over the past 20th century. Chronic corruption, fragile governance, cholera outbreaks and devastating natural events, such as the 2010 earthquake that claimed 250,000 lives and injured 300,000, have further exacerbated the nation’s instability. At the heart of this so-called multidimensional crisis on a catastrophic level lies a complex network of actors vying for power and influence.

The Haitian Crisis since 2018

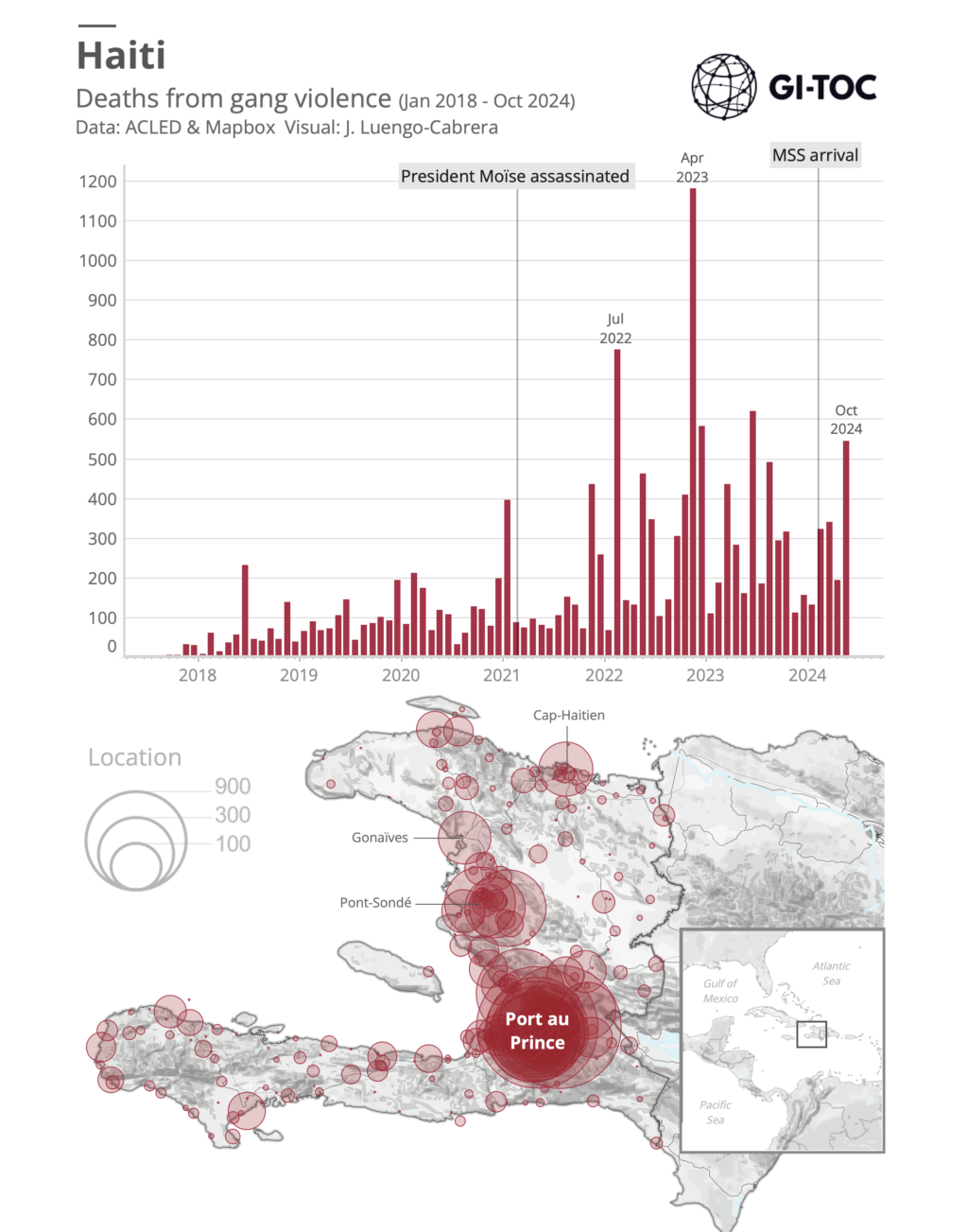

The roots of the current crisis can be traced to July 2018, when protests erupted over increased fuel prices and misappropriation of development funds, signalling growing discontent with the government’s economic policies. From 2019 to 2021, massive protests called for the government of President Jovenel Moïse to resign. Since then, a functioning parliament has not existed. The situation deteriorated rapidly in July 2021 with the assassination of Moïse by a group of assailants, including 26 former Colombian and two Haitian-American soldiers and individuals with political ties, creating a power vacuum that exacerbated existing political instability and a massive increase of gang violence.

Criminal groups or gangs, notably the G9 Alliance, have effectively usurped control over nearly two-thirds of the country. These gangs, often backed by wealthy businessman, position themselves as political actors, making demands of the government while resorting to extreme violence when their requests go unmet. The 2023 alliance between G9 and G-Pep under the name „Viv Ansanm“ („living together“ in Haitian Creole) marked a significant escalation in their bid to overthrow the government, while the Prime Minister Ariel Henry was looking for support in Kenya. A key player in this regard is the former police officer and G9-leader Jimmy ‘Barbecue’ Chérizier, who, despite his sometimes irrational and brutal behaviour, has demonstrated a high level of strategic competence, as evidenced by his repeated success in forming gang alliances.

By February 2024, protests demanding Henry’s resignation had intensified, reflecting widespread frustration with the lack of progress in addressing the country’s crises. The situation reached a critical point on February 29, 2024, with a wave of highly coordinated gang attacks by Viv Ansanm, the coalition of G9 and G-Pep, on political institutions, prisons and police stations in Port-au-Prince, leading to the declaration of a state of emergency on March 3, 2024. The escalation continued with an attack on the National Palace on March 8, 2024 by gang members, partly under the leadership of Jimmy Chérizier, forcing the closure of schools and government offices. This event underscored the government’s inability to maintain control and protect key institutions.

In response to the worsening security situation, the UN Security Council approved the Multinational Security Support (MSS) mission in October 2023, led by Kenya, to assist the Haitian National Police in combating gang violence. It is severely understaffed and outgunned, struggling to maintain order against these well-armed gang factions. Meanwhile, the recently remobilised Forces Armées d’Haiti (FAd’H), reestablished in 2017 after a 22-year absence, remains largely invisible in the current crisis.

Simultaneously to the uprising gang violence, the Transitional Presidential Council (TPC; French: Conseil présidentiel de transition; Haitian Creole: Konsèy Prezidansyèl Tranzisyon) was founded by different civil and political parties to organize fair and free elections for 2025, but has not presented a plan to fulfill this aim. However, the TPC, currently led by interim Prime Minister Alix Didier Fils-Aimé since November 2024, struggles to maintain legitimacy and control with respect to expanding gang activity. Its mandate expires when a new elected President takes office or on February 7, 2026. In the past, it was also characterised by corruption scandals. It is strongly divided, which is shown by its replacement of the appointed interim prime minister Garry Conille by Alix Didier Fils-Aimé after only five months in November 2024.

A Nation on the Brink

The situation in Haiti remains dire. Longstanding political volatility, undermining the rule of law and effective public finance, and massive corruption are pushing crime and impunity. Throughout 2024, gang violence has continued to spread beyond Port-au-Prince, with armed groups expanding their territorial control and influence. The United Nations Human Rights Office reported that 2024 was the deadliest year in Haiti’s recent history, with at least 5,626 people killed, 2,213 injured, and nearly 1,500 kidnapped due to gang violence. Gangs now control more than 85% of the capital Port-au-Prince and other key regions such as Ouest and Artibonite – Haiti’s agricultural heartlands. The brutal gang violence has “centrifugal dynamics” that have led to three large-scale massacres in the last quarter of 2024. In only one of them, 207 people were killed by guns or machetes. Over 20,000 people were displaced in just four days of November 2024. Critical infrastructure, including airports and seaports, is frequently targeted by gangs, severely impacting the delivery of humanitarian aid and essential supplies.

Source: Le-Cour-Grandmaison, R. (25 November 2024). “The latest storm makes groundfall in Haiti” Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC). https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/haiti-caught-between-political-paralysis-and-escalating-violence/ © Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime

The human cost of this crisis is staggering. Nearly 20,000 people in Port-au-Prince are facing catastrophic famine-like conditions. Only 20% of the town’s healthcare facilities are operational, and 40% nationwide. Children are particularly affected by violence, with many being forced into criminal groups due to hunger and poverty. The UN estimates that around half a million children live under the control of such groups, making up at least 30% of their members. Widespread food insecurity and lack of access to basic services have pushed the population to the brink. The ongoing violence, political and societal instability continue to pose significant challenges to efforts aimed at restoring order and implementing long-term solutions for Haiti’s crises.

International Involvement: A Double-Edged Sword

The role of international actors in the conflict in Haiti is complex and often contradictory. The United Nations, United States, Canada, and Kenya lead efforts to support Haiti’s security and governance. However, some of their involvement is not without controversy, as historical interventions have often prioritised foreign interests as well as the interests of particular domestic groups over Haitian sovereignty. Moreover, members of the previous UN stabilisation mission MINUSTAH (2004-2017) were accused of sexual abuse and also of being responsible for the cholera outbreak 2010. Following the completion of it, the UN Security Council established the UN Integrated Office in Haiti (BINUH) in 2019 to bolster political stability, good governance, and human rights. However, due to insufficient measures and the worsening security situation, the UN Security Council authorised the Multinational Security Support (MSS) mission in October 2023. Led by Kenya, the MSS was intended to assist the Haitian National Police in combatting gang violence for an initial 12-month period and was renewed in September 2024. However, the deployment has been hampered by funding and personnel shortages, with only around 400 of the planned 2,500 officers arriving in Haiti by December 2024.

The United States, Haiti’s largest trading partner, has historically intervened in the country, often prioritising its own geopolitical interests. Recent policies have focused on supporting Haitian law enforcement and providing humanitarian aid, but critics argue these efforts fail to address root causes of instability. The US involvement in Haiti is motivated by several key factors. Haiti’s proximity to the United States makes its stability a matter of national security. A stable Haiti is seen as crucial in preventing issues such as reducing the flow of Haitian migrants to its borders and transnational crime from affecting the US. Additionally, with Haitian exports to the US comprising more than 80 percent of Haiti’s total exports in recent years, economic interests play a significant role. Furthermore, supporting Haiti is viewed as a way to limit the influence of rival powers like China and Russia and to hence counter foreign influence in the Caribbean region. It is questionable how the role of the US will change under the new Trump administration, but a major part of the funding of the MSS mission has already been frozen.

Not ignored but still unsolved

In light of the various UN Security Council resolutions, the situation in Haiti can not really be described as completely ignored. In fact, it is relatively well recognised at the UN level and in the media of the Global North. However, the question remains: why does the international community, particularly former colonial powers, consistently fall short of pursuing comprehensive stabilisation and conflict resolution measures? One explanation lies in the harsh reality of the current geopolitical climate, where major donor countries assign a low priority to Haiti. This is evidenced by the underfunding of critical organisations like UNICEF and OCHA. Furthermore, a more robust response would require states such as France to confront their historical culpability, potentially including addressing the issue of “compensation payments” extracted from Haiti. However, as previously mentioned, the current French leadership demonstrates no willingness to assume this responsibility and to implement more substantial measures to address the crisis.

A Challenging Path Forward

The future of Haiti remains uncertain, but there are potential avenues for progress. Efforts to restore political stability and combat corruption are crucial, as is increasing support for humanitarian aid and economic development. The process of political stabilisation must be carefully planned. This includes holding free and fair elections and strengthening democratic institutions. But in the context of the shared responsibility of the political leaders and the members of the TPC for the current situation, these necessary reforms are as questionable as they are currently unfeasible regarding the situation of violence. As a starting point for such reforms, a degree of internal security must be established. Even if this will not be possible due to your use of foreign forces. A comprehensive security definition is central here. Derived from this, not only security forces, but also forces of the civil emergency services and humanitarian aid should be involved. To prevent the difficulties of previous foreign interventions, civil society international organisations are to be involved on an equal footing. Premature elections without adequate structures and legitimate candidates could be counterproductive. It is important to find a way to deal with existing criminal structures without further endangering stability. The question of whether and to what degree gangs and their leaders should be included in this process also remains open. Moreover, addressing Haiti’s economic woes requires a comprehensive and long-term approach, including debt relief, investment in infrastructure, and support for local industries. This approach is again predicated on the willingness of the international community to pursue a sustainable solution process.

Despite international attention, Haiti’s crisis demands urgent continued humanitarian assistance and action from both the international community and Haitian civil society. As Marie-Marcelle Deschamps, a Haitian doctor and humanitarian, aptly states: “Haitians will support a proper restoration of security, which is our urgent first step now”. Initiatives like the Youth Advisory Committee (French: Comité Consultatif de Jeunes, CCJ) offer hope, enabling young Haitians to actively engage in peace-building efforts and offering them a voice in shaping their communities‘ future. This initiative, part of the “Seeds of Peace” project, creates a space for youth to advise on development strategies, contribute to impact assessments, and participate in dialogue with state authorities. By fostering youth leadership and representation in volatile areas like Cité-Soleil, Bel-Air, and Saint-Martin, these programs aim to reduce gang influence and provide alternative paths for social advancement.

However, any sustainable solution must address the historical injustices and structural inequalities that have long plagued the nation. True resolution hinges on confronting the root causes of instability, including systemic poverty, corruption, and the enduring legacy of colonial exploitation. The international community, and especially former colonial powers, must acknowledge their role in Haiti’s current predicament and provide meaningful support for long-term development and stability. A comprehensive approach that combines long-lasting investment in security measures, political reforms, economic development, and grassroots empowerment is essential for Haiti to break free from its cycle of crisis and build a more stable and prosperous future. Crucially, the success of the MSS mission depends on learning from and addressing the failures of past international interventions such as the pursuit of integrated state-building approaches involving security forces and civil society groups.

Elanur Alsaç (she/her) is the co-head of the “Peace & Conflict” program of Polis180. She studied social sciences in Berlin and London and is currently completing her Master’s degree in Political Science in Berlin. In addition to peace and conflict research, her main areas of interest include global foreign and security policy, transatlantic relations and climate security.

Carlos Apel (he/him) joined Polis180 in 2024 and is participating in the EUROMAT project as part of the Polis180 campaign for the 2025 German federal elections. He studied Politics and Law with a focus on European and international issues in Münster, Dublin and Berlin. His research contains mainly topics in the field of international security, arms control and European studies.

Previously from the blog series “Ignored Conflicts”

-

Between Neocolonialism and Jihad: The Overlooked Conflict in Burkina Faso

-

From Revolution to Ruin: Haiti’s Plight and the World’s Apathy

-

The High Cost of Ignoring Nagorno-Karabakh: How Unresolved Grievances and Geopolitical Interests Fuel Future Conflict

-

The Unfinished Breakaway: Why Somaliland Matters to Global Stability

-

Raw materials, rebellion, Rwanda: The multilateral crisis in eastern DR Congo and its global implications

The Polis Blog serves as a platform at the disposal of ‘Polis180’s & ‘OpenTTN‘s members. Published comments express solely the ‘authors’ opinions and shall not be confounded with the opinions of the editors or of Polis180.

Zurück