space

Eastern Partnership – How did we get there?

A brief introduction

“Our neighbours‘ strength is also the European Union’s strength” – these were the words of the European Union’s (EU) High Representative Josep Borrell when he presented the first outline for future objectives of the Eastern Partnership (EaP) beyond 2020.

The EaP constitutes the policy-framework through which the EU develops its relations with its Eastern neighbours, namely Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, the Republic of Moldova, and Ukraine. Its main goal, according to its founding documents, is to “create the necessary conditions to accelerate political association and further economic integration between the European Union and interested partner countries.”

Borrell’s words underscore the centrality of this region for the future of the European Union. His words can be interpreted from an economic, political, and even geopolitical standpoint. These countries matter. So how can the EU live up to the expectations, Borrell’s choice of words inevitably sets?

Since its inauguration in 2009, more than ten years have passed. In order to make it fit for the future, the EU is currently undergoing a “consultation process” reviewing the EaP’s strategic direction. Results of this endeavour are to be endorsed by the member states in June 2020.

It is therefore high time for an interim evaluation. This publication, however, seeks not to ruminate on high-level statements and policy talk from the Brussels bubble. It seeks, instead, to bring in grassroots perspectives from people on the ground. Therefore, we have asked young thinktankers and politics enthusiasts in all EaP countries to share with us their views on this European initiative. The following contributions draw a differentiated picture of how the EaP is perceived, what its flaws and virtues really are, and what expectations exist in different national contexts for relations with the EU in the years to come.

But first, let’s briefly recap what the EaP is and how it fits into the EU’s clutter of agreements and frameworks. In the 1990s, the EU – having just started to take the foreign policy dimension more seriously[1] – signed Partnership and Cooperation Agreements (PCAs) with the newly independent post-Soviet republics in the East. These agreements facilitated cooperation in areas such as economics, politics, science, and culture. Employing conditionality[2] to stimulate reforms and the adoption of EU-norms, PCA’s were an instrument to push for further integration into the EU.[3]

In 2004, shortly after its biggest enlargement to date[4], the EU launched the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP). Designed “to create a ring of friends” around the Union’s borders, the ENP constitutes a broad umbrella framework for cooperation with neighbouring countries in the East and South of the Union.

Here is where the EaP comes in: initiated by Poland and Sweden, the EaP was introduced as a distinct dimension of the ENP focusing on six countries in the East.[5] It seeks to build “a common area of shared democracy, prosperity, stability and increased cooperation”. The EaP as a whole is meant to be a major driver of structural reforms in the region, as well as economic integration and political association with the EU. It remains, however, short of an explicit promise for EU membership. Focal points have been cooperation on trade issues, economic development, visa liberalization, and human rights. The EaP’s major evolution from the ENP framework lies in its dual approach, combining multilateral cooperation – within the region – and bilateral relations between individual EaP countries and the EU.[6]

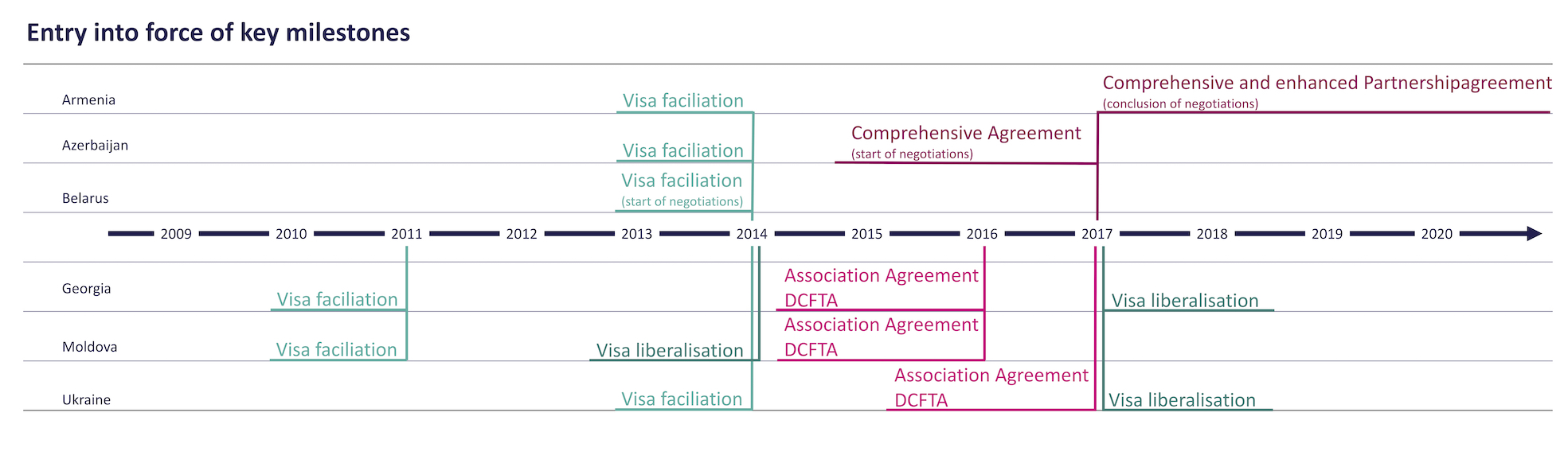

Important instruments within the bilateral sphere are so-called Association Agreements (AAs), which are complemented by Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Areas (DCFTAs). AAs envisage especially close economic and political cooperation.[7] Fully implemented, associated countries would “align their policies with around 80-90% of the acquis communitaire[8], including economic, legal and regulatory convergence with EU standards”.[9] Among the EaP countries, only Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia have signed AAs so far.

Additionally, in 2017, the six EaP countries together with the EU committed to “20 deliverables for 2020”, a work plan for reforms in the areas of economy, governance, connectivity, and society more broadly. Now that this benchmark year has been reached with the EaP celebrating its tenth anniversary, the EU takes the initiative to assess progress on the deliverables and to agree on aims for the future.

So where are we today with the EaP? Besides the manifest achievements and overall success, challenges like corruption, slow reform progress, as well as conflicts within and among partners remain. At the same time, levels of cooperation differ greatly among the individual partner countries – leading some to call for a more differentiated approach. Other factors to take into account include the wider international arena – most notably Russia whose government has repeatedly accused the project of drawing a dividing line between Russia and its neighbours – and unresolved territorial conflicts exist in all EaP countries (except Belarus.)

The six contributions which follow seek to shed light on the EaP from different national angles, highlighting the particularities of each partner country and addressing important issues that need to be considered when discussing the initiative’s future.

All authors welcome that the EU focuses on its Eastern neighbours and the geopolitical fragility of the region. The six countries have all benefited in some form from the EaP. Kateryna Zarembo and Mariam Tsitsikahsvili observe in Ukraine and Georgia respectively that the DCFTAs and visa free regimes have brought the most tangible results to ordinary citizens and smaller businesses. Furthermore, pressure from the EU has led to some necessary administrative reforms. One example of this is the reform of the Electoral Code in Armenia which was regarded as a success by Hasmik Grigoryan.

However, the authors wish for a more individually tailored approach of the EU towards their countries. Their recommendations on those changes derive from their countries’ experience with the EaP which cannot be summarized as a linear success. Indeed, Azerbaijan chose to downgrade its effort of integration to a loose cooperation, observes Rusif Huseynov. In the case of Yerevan, the EU was able to sign a cooperation agreement albeit without free trade element. As Hasmik Grigoryan underlines, this was still an important signal for pro-European actors in Armenia. On the other end, the EU should not ignore the ambitions of the more advanced partner countries that strive for even further integration.

The EU should not overlook windows of opportunity when it comes to cooperate with governments or civil society actors in the EaP countries. The EaP should focus on the strongest contributions it could bring to each of the six countries.

_________________

[1] The „Common Foreign and Security Policy“ was established with the Treaty of Maastricht in 1993.

[2] “Conditionality” means that third countries need to commit to the fulfillment of certain (reform-, democratization-, human rights-) conditions in order to benefit from closer ties with the EU.

[3] Casier, Tom. 2016. ‘From Logic of Competition to Conflict: Understanding the Dynamics of EU–Russia Relations’. Contemporary Politics 22(3): 376–94. p.381.

[4] With the ‘record’ Eastern enlargement of 2004, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Malta and Cyprus became members of the European Union.

[5] Russia from the very beginning decided not to join the ENP.

[6] Amaro Dias, Vanda. 2018. ‘The Battle of Giants: The Collision of EU and Russian Foreign Policies towards the Contested Neighbourhood and the Ukrainian Crisis’. Debater a Europa (18): 63–83. pp.66-67.

[7] Casier, Tom. 2016. ‘From Logic of Competition to Conflict: Understanding the Dynamics of EU–Russia Relations’. Contemporary Politics 22(3): 376–94. p.387.

[8] The whole body of European Union law, including the Treaties, legislation, court decisions, declarations and resolutions.

[9] Amaro Dias, Vanda. 2018. ‘The Battle of Giants: The Collision of EU and Russian Foreign Policies towards the Contested Neighbourhood and the Ukrainian Crisis’. Debater a Europa (18): 63–83. p.67.

Click to enlarge!

Image source: own illustration

space